Sabrina Carpenter has released the art for her upcoming album Man’s Best Friend, and, predictably, it has bought the puriteens out of the wood work yet again.

I wrote about puriteens and their specific hatred of Sabrina Carpenter last year, but I fear I have to pen yet another piece defending a white woman I don’t even care about because internet discourse feels particularly obtuse at the moment.

In case you missed it, the image that has provoked such spirited debate online is of Sabrina Carpenter on all fours, mouth open like a dog panting, next to a faceless man in a suit who is holding a fistful of her hair like a leash. Alongside this image is another of a faceless dog in a collar, and the title of her album “Man’s Best Friend”.

Since this image has released, Sabrina Carpenter has been accused of all manner of feminist crimes including “centring men”, “setting back feminism 100 years”, and the usual hullaballoo regarding her hypersexual persona. While these criticisms aren’t surprising, it does disappoint me that so many of them are based on “feeling icky” rather than an interesting breakdown on what her art means and represents.

My interpretation of Carpenter’s message is that she is making a commentary on the expectations men have of the women in their life and how these expectations are similar to the ones that they have of their dogs: subservience, obedience and a will to please. To be a man’s best friend, either as his dog or his wife, requires a level of domination and acceptance of a “master”.

Presenting herself as a dog — a female dog, a bitch — on a lead is subversive, at least from my understanding of it, because in all her other art she represents herself as a woman with sexual agency (to the point that it pisses people off). It’s because of this that I don’t read her latest album cover as an endorsement of the dehumanisation of women, but a playful jab at it. Given “Please please please” — a song about the way a man disappoints and humiliates Carpenter — is her most popular hit, it feels deliberately obtuse to assume Carpenter has no understanding of power dynamics and is unaware of the “degrading” nature of kneeling for a man.

Of course, I can’t say exactly what Carpenter is conveying because I can’t read her mind, but it’s concerning to me that so many people can see this provocative image and take it literally and at face value, instead of considering what the imagery represents, and why those images would be chosen especially in the wider context of puritanism around Carpenter specifically.

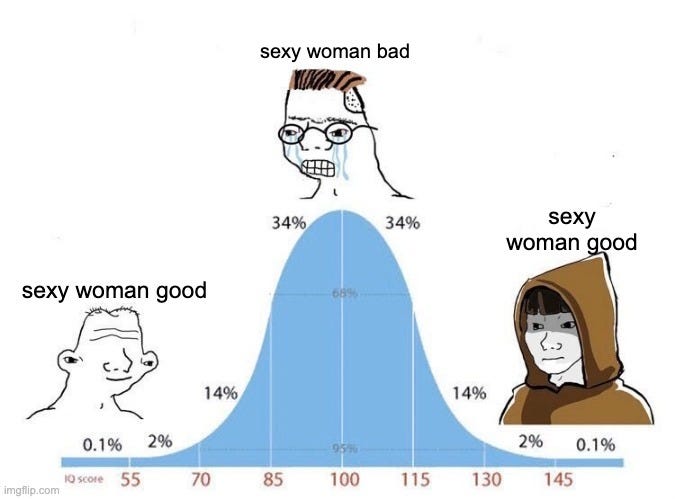

However, this widespread backlash is not simply based on some misunderstanding of Carpenter’s politics — I believe it to be a symptom of the “literalism” epidemic we are suffering at the moment.

The term first appeared in my vocabulary thanks to writer Namwali Serpell, who wrote about “the new literalism plaguing today’s biggest movies” for the New Yorker. Mitch (my husband) showed me this essay after I made him watch Jurassic World Dominion (2022). One of my (many) complaints about this, quite frankly offensive, film is that it refuses to have any subtext — everything is literal and so painfully on the nose that the movie is sexless, insipid and boring, especially when it comes to the relationship between Dr Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and Dr Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern).

In the original Jurassic Park (1993) — the best movie ever I think — the two are clearly a couple (or, at the very least, sleeping together) and we don’t need them to kiss and profess their love for each other to know it. There are little moments: lingering looks, cheeky comments, a hand on a butt, Alan getting annoyed at Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), that signal to us something is going on between these two. Their relationship is one of my favourite parts of the story because the subtext is so rich. However, this is all set on fire and burned to ashes in Dominion, which ramps up their romance to the point where it feels corny, a caricature of itself. It’s like the filmmakers don’t believe the audience is capable of putting two and two together, and so we must be shown and told of every development to make sure its hammered home. As Serpell argues via the iconic Family Guy meme, a film like this is “condescending” and “insists upon itself.”

In fact, subtext is what makes analysis fun as a fan of a movie/franchise/fictional world. As Henry Jenkins put it in his iconic essay “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching”, “For fans, reading becomes a type of play, responsive only to its own loosely structured rules and generating its own pleasure.” Subtext is what gives you room to interpret and play with characters and settings. It’s what allows things like headcanons and fanfic to be born — people are able to take a bit of subtext and run with it, creating new media and interpretations of relationships and events.

“‘Fandom’ is a vehicle for marginalised subcultural groups (women, the young, gays, etc.) to pry open space for their cultural concerns within dominant representations; it is a way of appropriating media texts and rereading them in a fashion that serves different interests, a way of transforming mass culture into a popular culture.”

— Henry Jenkins, “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching”, Critical Studies in Mass Communication (1988).

Funnily enough, at the same time as this “literalism” crisis, I’ve also seen complaints in fandom about younger Gen Z* entering these spaces and not having fandom etiquette, probably as a result of being so “it’s not that deep”-pilled. These new members of fandom are harshly critical of people who ship two characters who aren’t canon, or of those who invent headcanons that aren’t perfectly in line with the confirmed events of the story, because they are so literal in their consumption of media. (*yes, yes, not all Gen Z, etc etc. I’m Gen Z too!)

To bring this tangent back to the discourse around Sabrina Carpenter, I do think that years of consuming cookie cutter media and art that refuses to play with subtext and therefore interpretation is what has led to a cultural moment in which images are perceived and analysed in the most literal sense. Depiction of a relationship or moment in history is considered endorsement, because we see showing and believing as the same thing.

“It’s hard to say which came first: our so-called media illiteracy or the dumbing down of the media. Complaints about our inability to read, interpret, or discern irony, subtlety, and nuance are as old as art. What feels new is the expectation, on the part of both makers and audiences, that there is such a thing as knowing definitively what a work of art means or stands for, aesthetically and politically. This strikes me as a blatant redefinition of art itself.”

— Namwali Serpell, “The new literalism plaguing today’s biggest movies”, the New Yorker.

Are we really going to assume Sabrina Carpenter is anti-feminist just because she’s sexy, and men like sexy? Are we going to assume that being a sexy woman who plays into kink and fetish makes her just as much of a perpetrator of misogyny as she is a victim of it?

It’s totally fine to argue that what Sabrina Carpenter is doing does not work. You are welcome to dislike her or feel like her content is hypocritical given she both critiques and enjoys hypersexuality. Personally, I could not care less about Sabrina Carpenter because I am not a fan and don’t listen to her music or follow her career. But what I must advise against is literalism and a refusal to consider context and subtext when analysing a pop culture moment.

Hate her or love her, but do it with reason and back your arguments with actual analysis, instead of “it makes me feel icky.” Art can be interpreted infinitely, and art eliciting a feeling in you — even a negative one — means it is doing its job.

I hadn't come across the term literalism before which much more convenient than saying ‘conflating depiction with endorsement’

Great writing as always!

Such a great piece! 👏❤️